Padua

Padua

Bembo’s family had a villa in the Paduan countryside (Santa Maria di Non), where Pietro spent time since he was young and often mentioned in his letters. At the beginning of 1522, he settled in the city of Padua together with his lover Morosina. In 1527 he bought the present Palazzo Camerini, where he moved with Morosina and their children Torquato and Elena in 1532. Appointed cardinal, he left for Rome in October 1539, leaving his children in Padua under the guidance of his friend and collaborator Cola Bruno.

Music in Padua

Padua had been under Venice’s domination since 1405 and therefore had no court. Music did not center around a specific place; instead, it was made in different places and at various social levels. Music was often heard during public ceremonies and festivities, both religious and secular; groups of wind players were usually required to play during such events. The Carnival period was particularly rich in music and dances, which sometimes were part of theatrical performances.

Archival documents show that many families had instruments at home, especially lutes. Music was also taught at the university, and students, both Italian and from abroad, sometimes took private lessons from outstanding musicians active in the town, like the lutenist Antonio Rota. The Paduan market for lute music was so crucial that the Venetian printer Girolamo Scotto would later publish ten volumes of lute tablatures (issued between 1546 and 1549), of which one was assigned to the abovementioned Antonio Rota, and five to the Paduan priest Melchiorre de’ Barberiis. Barberiis’s volumes were dedicated to distinguished city personalities, including Bembo’s son Torquato.

One of the most important venues for Padua-based intellectuals was the “corte” of Alvise Cornaro, a Venetian architect and patron of the arts, which included the Loggia and the Odeo. The Loggia, built in 1524 on a project by Antonio Maria Falconetto, was intended as a frons scenae for theatrical performances, which often contained musical intermedi. The Odeo, erected in the 1530s, was specially conceived for music and discussions among intellectuals. The decoration of one of its rooms comprises Pietro Bembo’s coat of arms, surmounted by the cardinal’s hat.

Bembo and music

Bembo was a close friend of Alvise Cornaro and frequented his “corte”. In a letter to Cornaro he expressed admiration for Ruzzante and surely attended performances of his comedies, which also contained music. On

6 June 1523

Bembo wrote to Benedetto Mondolfo in Urbino to recommend to the duke Francesco Maria I Della Rovere two lutenists, Bernardo Fiorentino and his son Flaminio, whom, according to his words, were worthy of being dear to any king. Nothing is known concerning these two musicians or their relationship with Bembo. Surely he knew them well and appreciated their music since he interceded for them. Even if, for the moment, no evidence has been found, Bernardo Fiorentino might be the “Bernardo de Liuto” mentioned in Lorenzo di Filippo Strozzi’s account book.

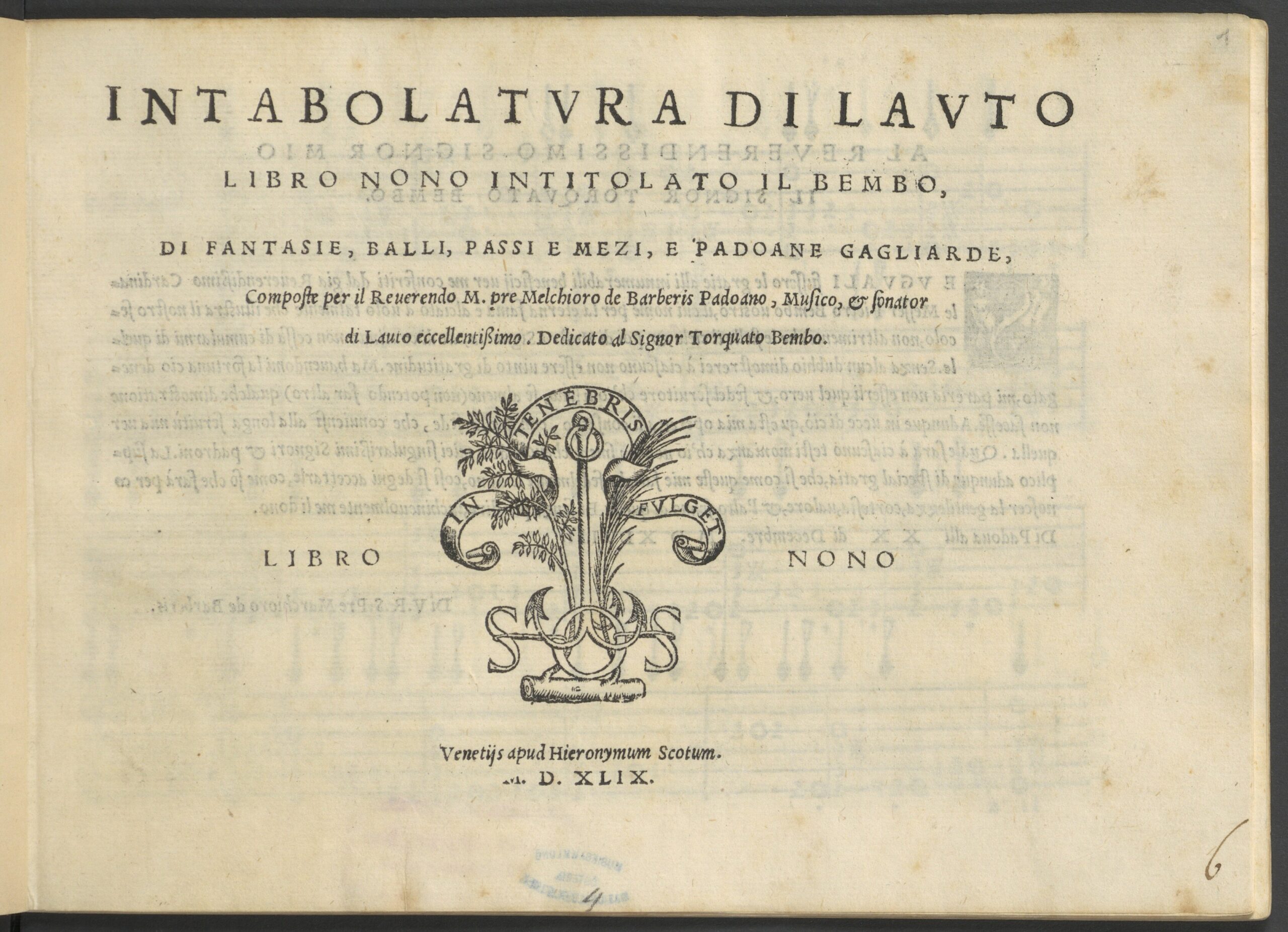

It is likely that the organist Marco Antonio Cavazzoni (who first met Bembo in Urbino and then in Rome) entered Bembo’s service in Padua. In the dedication to Bembo of his Intavolatura cioe recercari canzoni himni Magnificati… Libro primo, published in 1543, Marco Antonio’s son Girolamo stated that he was born when his father was at the service of Bembo, who had also been his godfather. Unfortunately, Girolamo’s date of birth is unknown. After Bembo’s death, two musical collections by Paduan composers were dedicated to his son Torquato: Melchiorre de’ Barberiis’s Intabolatura di lauto libro nono intitolato il Bembo (1549) and Francesco Portinaro’s Il primo libro de madrigali a cinque voci (1550). Barberiis, as he himself states, was at the service of Bembo’s family at some point, even if the details remain unknown. Portinaro’s collection, instead, contains an interesting madrigal, Sacro signor, whose text wishes Torquato to follow in his father’s footsteps, and explicitly mentions the name of “Torquato”, ending with the repetition of the words “Pietro Bembo”.

Jacques Arcadelt, Quand’io penso al martire (Il primo libro di madrigali… a quatro, Venezia 1539)

Choir of King’s College, Cambridge, Stephen Cleobury

Melchiorre de Barberiis, Fantasia sopra “Se mai provasti donna” (Intabolatura di lauto… libro nono, Venezia 1549)

Franco Fois

Antonio Rota, Fantasia 67 (Intabolatura de lauto… libro primo, Venezia 1546)

Luca Pianca

Credits

city map

Bernardino Scardeone, De antiquitate urbis Patavii, Basel, 1560

credits: München, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, 2 Ital. 151 a (https://www.digitale-sammlungen.de/en/view/bsb10144306?page=6,7)

NO COPYRIGHT

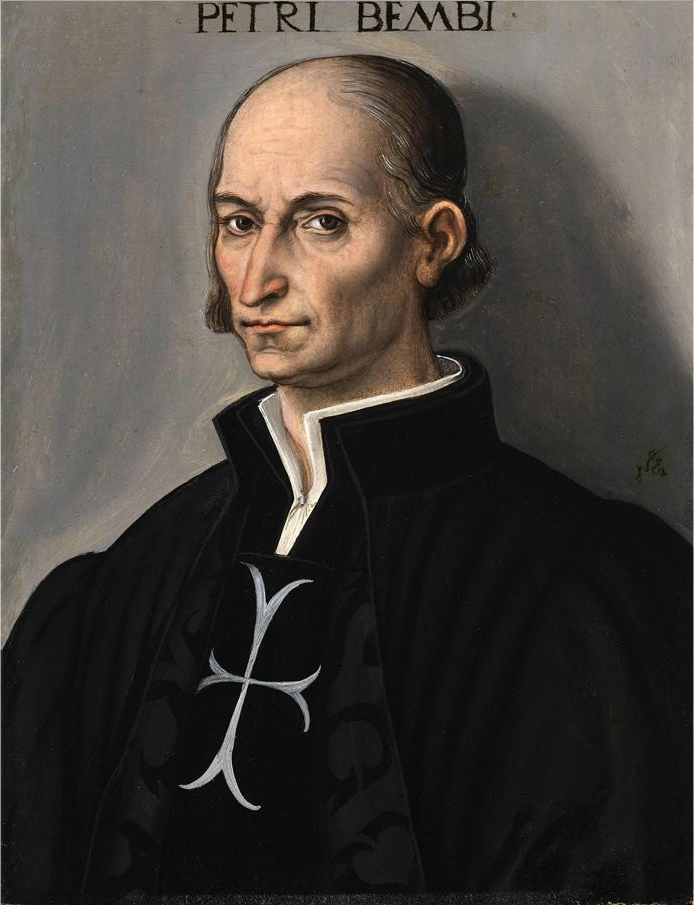

fig. 1

Lucas Cranach the Younger, Pietro Bembo, c. 1532-1537 (collezione privata)

Credits: Lucas Cranach the Younger, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Pietro_Bembo_by_Cranach_the_Younger.png)

fig. 2

Melchiorre de Barberiis, Intabolatura di lauto libro nono intitolato il Bembo (Venezia, 1549).

Credits: Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, SA.76.F.17/9 MUS MAG (https://onb.digital/result/131B1156)

Fig. 3

Sebastiano Florigerio, Musikalische Unterhaltung, 1530s (München, Alte Pinakothek)

Credits: München, Alte Pinakothek http://www.sammlung.pinakothek.de/de/artwork/QrLWzg0xNO/sebastiano-florigerio/musikalische-unterhaltung

CC BY-SA 4.0