Rome

Rome

Pietro Bembo moved to Rome at the beginning of 1512. The following year he became secretary of the new Pope Leo X, together with his friend Jacopo Sadoleto, and stayed at his service until Leo X’s death in 1521. However, due to health problems and family reasons, Bembo left Rome in May 1519 for about a year and again in April 1521 and was not there when Leo X died in December. Early in 1522, Bembo settled in Padua, where he stayed until 1539; after becoming a cardinal, he returned to Rome in October of that year. He died there on 18 January 1547 and was buried in the Church of Santa Maria sopra Minerva.

Music in Rome (1512-1521; 1539-1547)

Giovanni de’ Medici, who became Pope Leo X in March 1513, particularly appreciated music and was himself a musician: he played the lute and harpsichord and even composed a few pieces. He probably studied with Heinrich Isaac, who celebrated him in his motet Optime pastor.

Besides the papal chapel, Leo X also had a private chapel at his disposal (the so-called “cantores et musici secreti”), which played during his meals and at his will. Coeval accounts also list private festivities organized in Leo X’s court in which music was performed. The well-known keyboard composer Marcantonio Cavazzoni served the Pope from April 1520 to February 1521, and Leo X reportedly admired his way of playing keyboard instruments.

In Rome, music was heard during festivities, like Carnival and the feast day of SS. Cosmas and Damian, and was also performed during theatrical performances. Indeed, during Carnival 1519, Leo X was able to attend the performance of Ludovico Ariosto’s Suppositi, which contained musical intermedi between the acts. Despite the loss of the music itself, coeval reports provide information about the instruments used on that occasion (shawms, crumhorns, cornetts, violas, lutes, organetto, flute, voices).

Poetry was often improvised on musical accompaniment. One of the best-known improvisers of Latin texts in Rome, Raffaele Brandolini, had written on demand of the future Pope Leo X a treatise on the practice of improvisation, De musica et poetica (presented to him in 1513), in which he defended extemporary performances from their detractors. Solo songs accompanied by lute, lyre or viola da braccio were also heard in academies. One of the most famous was that of Johannes Goritz, which counted among his members humanists (such as Baldassarre Castiglione) and musicians at the service of Leo X (Andrea Marone da Brescia, Gentile Santesio, Giovanni Battista Casali, and Francesco Sperulo).

Under the papacy of Paul III (1534–1549), the papal chapel included some of the most renowned composers of the time, such as Jacques Arcadelt, Costanzo Festa, and Cristobal de Morales.

Bembo and music

When Bembo was secretary to Leo X, he certainly took part in feasts and attended theatrical performances organized for the Pope. Thanks to his position, he also had links with composers and people associated with the musical world. Among other things, in 1513, he signed the printing privilege that the music printer Ottaviano Petrucci requested from the Pope. A few musicians (the lutenist Giovanni Maria Alemanni, the keyboard player Vincenzo da Modena, the composer Francisco de Peñalosa, and the singers “Michelem Lucensem”, “Bernardum Agriensem” and a not named “puerum […] Gallum Musicae artis peritum”) are mentioned in the Brevi, short letters in Latin that Bembo wrote on behalf of the Pope and later reworked and published. Bembo also met again the organist and composer Marco Antonio Cavazzoni, whom he had known since his stay in Urbino. Bembo is also listed among the members of Goritz’s academy.

As for Bembo’s second stay in Rome, he likely came into contact with the composers and singers active in the papal chapel, like Jacques Arcadelt; unfortunately, no evidence is extant. Although Bembo left his children in Padua, he continued to be concerned about their upbringing. Regarding music, two letters (

17 October 1540

and

10 December 1541)

addressed respectively to Cola Bruno and to Elena herself) attest that Bembo, following a widespread prejudice of the time, prevented Elena from learning to play the clavichord, stating that making music was inappropriate for a woman of her class.

The only known reference to Bembo’s singing dates back to this period: writing to Trifone Gabriele on

3 January 1544

Bembo told him that, if he had been there, he would have heard him not only saying a Mass but also singing it.

Marco Antonio Cavazzoni, Salve virgo (Recerchari motetti canzoni libro primo, Venezia 1523)

Liuwe Tamminga

Mouton, Queramus cum pastoribus (Città del Vaticano, MS Capp. Sist. 46, c. 1508–1527)

Sistine Chapel Choir, Massimo Palombella

Philippe Verdelot, Se mai provasti donna (Libro primo de la fortuna, Roma c. 1526)

Profeti della Quinta

Philippe Verdelot, Se l’ardor foss’equale (Madrigali de diversi musici. Libro primo de la serena, Roma 1530)

Profeti della Quinta

Credits

city map

Hartmann Schedel, Registrum huius operis libri cronicarum cum figuris et ymagibus ab inicio mundi, Nüremberg, 1493, c. 57v

Credits: München, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Rar. 287 (https://www.digitale-sammlungen.de/en/view/bsb00034024?page=184,185)

CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

fig. 1

Raffaello Sanzio, Parnaso, 1510-1511, Città del Vaticano, Palazzi Vaticani, Stanza della Segnatura

Credits: Raphael, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Raphael2.jpg

fig. 2

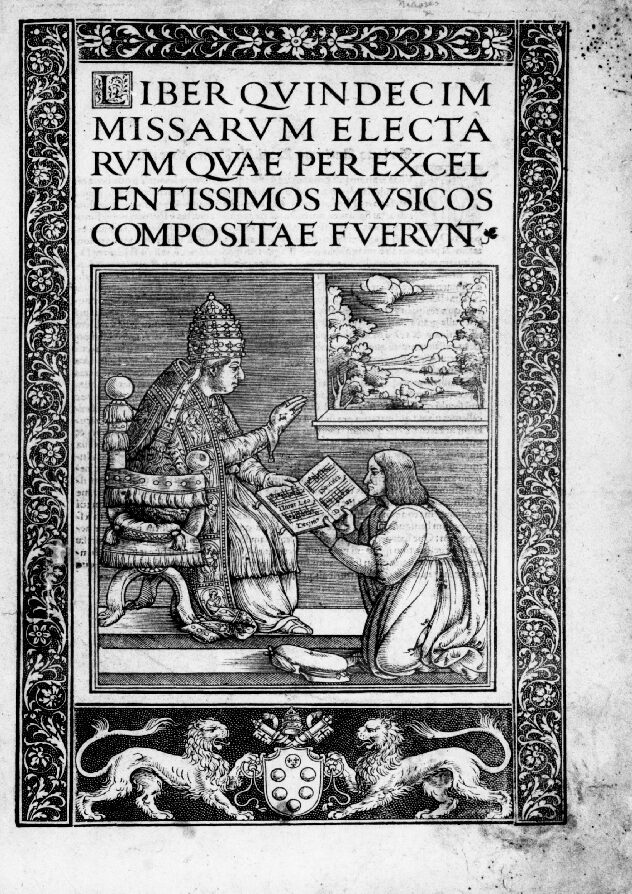

Andrea Antico, Liber quindecim missarum (Roma, 1516), frontespizio: Antico presenta il volume a Leone X

Credits: University of London, Senate House Library (https://imslp.org/wiki/Liber_quindecim_missarum_(Antico,_Andrea)#IMSLP307727)

CC BY-SA 4.0

Fig. 3

Filippino Lippi, Assunzione della Vergine, 1489-1491, Roma, Santa Maria della Minerva, cappella Carafa

Credits: Peter1936F, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Santa_Maria_sopra_Minerva;_Cappella_Carafa;_Himmelfahrt.JPG